Can the FDA Regulation of Medical Devices Work Without Full Disclosure?

Bloomberg has an interesting article today discussing medical device approval and where the fault lies for bad devices being approved for use.

The Food & Drug Administration (FDA) “approves” medical devices and often (some say too often) grants review and approval under Section 510(k) of the Food, Drug & Cosmetic Act. Commonly referred to as “Premarket Notification” within the industry, it is remarkable the devices that are approved for use on consumers with little or, often, no testing.

Under the 510(k) regulations, the device must be “substantially equivalent” to other similar devices already approved by the FDA and on the market. “Substantially equivalent” has a somewhat broad definition:

“The term “substantially equivalent” is not intended to be so narrow as to refer only to devices that are identical to marketed devices nor so broad as to refer to devices which are intended to be used for the same purposes as marketed products. The committee believes that the term should be construed narrowly where necessary to assure the safety and effectiveness of a device but not narrowly where differences between a new device and a marketed device do not relate to safety and effectiveness. Thus, differences between “new” and marketed devices in materials, design, or energy source, for example, would have a baring (sic) on the adequacy of information as to a new device’s safety and effectiveness, and such devices should be automatically classified into class III. On the other hand, copies of devices marketed prior to enactment, or devices whose variations are immaterial to safety and effectiveness would not necessarily fall under the automatic classification scheme.”

The FDA sets forth the elements constituting “substantial equivalence” as:

A device is substantially equivalent if, in comparison to a predicate it:

- has the same intended use as the predicate; and

- has the same technological characteristics as the predicate;

or- has the same intended use as the predicate; and

- has different technological characteristics and the information submitted to FDA;

- does not raise new questions of safety and effectiveness; and

- demonstrates that the device is at least as safe and effective as the legally marketed device.

A claim of substantial equivalence does not mean the new and predicate devices must be identical. Substantial equivalence is established with respect to intended use, design, energy used or delivered, materials, chemical composition, manufacturing process, performance, safety, effectiveness, labeling, biocompatibility, standards, and other characteristics, as applicable.

So, the general nature of the definition has a foundation in good intentions. The process is intended to protect the consumer, but to not unduly delay technology that has already been tested and should be expediently approved for use on consumers.

The process in place for medical device approval is simply a very slippery slope.

Under FDA regulations, a device can also be considered appropriate for “expedited review if:

- (It) is intended to treat or diagnose a life-threatening or irreversibly debilitating disease or condition.

- The device represents a breakthrough technology that provides a clinically meaningful advantage over existing technology.

- No approved alternative treatment or means of diagnosis exists.

- The device offers significant, clinically meaningful advantages over existing approved alternative treatments.

- The availability of the device is in the best interest of patients.

So, what is at the heart of the 510(k) “substantially equivalent” device approval process? Honesty, candor and transparency must be a central part of it or the process will not work and unsafe devices will be released for use on unsuspecting consumers.

Cardiovascular medical devices have accounted for a third of FDA recalls and many of those devices were originally approved through the 510(k) process. Most recently, a Johnson & Johnson company, Depuy Orthopedics, recalled 93,000 hip implants suspected of unaccounted for failure and the risk of releasing dangerous levels of cobalt and chromium into patients’ bodies.

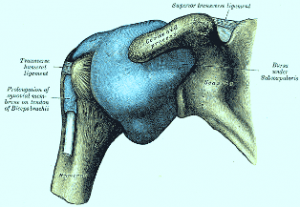

Perhaps one of the “poster children” for 510(k) failure were intra-articularly placed pain pumps designed to inject pain killers, like bupivacaine, directly into patient joint spaces immediately after surgery. There is nothing wrong with using bupivacaine during surgery to bathe the wound site and provide for some pain reduction in the tissues immediately adjacent to the surgical site. In addition, there is nothing particularly wrong with machines that gauge the injection of pain killers into patients in an effort to both relieve pain and to control patient addiction to the drugs.

What was wrong was the way in which pain manufacturers attempted to get their new machine approved and the untested way in which they knew they would be recommending their device to be used. The various manufacturers submitted 510(k) approvals and provided documentation that their products were substantially equivalent to other similar devices already on the market. Was that true; did their statements come with candor and transparency? Well, the 510(k) submissions were, one could argue, truthful; at least as far as they went in disclosing facts. Unfortunately, it can be fairly said that the manufacturers failed to disclose “the rest of the story”.

The FDA approved the devices, but at least in one case, the FDA specifically forbid the use of the device in orthopedic patients. What the manufacturers did not fully inform the FDA about was their intentions to instruct for use of the device in post operative orthopedic patients by, for the first time, recommending the injection of pain killer directly into the joint spaces. They did not disclose to the FDA they intended to launch intensive marketing campaigns and recommend that physicians implant the drug delivering device into the joint space, but fail to disclose to the physicians that this process had never been tested for safety. They forgot to tell the FDA they would be holding seminars to explain to physicians the best methods for using the pain pumps in the joint space. That entire physician targeted presentations would be disseminated to teach physicians the best ways to code the use of their device in order to get insurance company or Medicare approval for this previously unknown treatment (check out Medicare Definition).

As a result, hundreds of, typically very young, athletic patients were sentenced to additional surgeries on their joints; in some cases surgeries requiring complete joint replacements more than once during their lifetimes.

The pain pump manufacturers have tried to justify their actions with a “who knew” defense. They claim that no reliable scientific evidence existed that would have provided warning for the use to which they recommended their device.

That is not entirely accurate either. At least one study did exist before the pain pumps received approval that should have caused concern for everyone. That study was not a part of any manufacturer’s submissions to the FDA. But, largely insufficient studies existed because the pain pump manufacturers failed to fully disclose how they intended to use their devices and failed to tell the FDA that the use was a new, untested and novel approach. It was the failure on the manufacturers themselves to conduct premarket testing and evaluation that created the lack of studies and their deceptive defense.

Did the system fail? Yes and no. One might argue that had all the procedures been followed and all regulation complied with, the system would have worked quite well. So, should we criticize the FDA for their failure to ask just the right questions or should manufacturers of recalled devices be held accountable for “honesty, candor and transparency”… or the lack thereof.

Share This